Science Works, part 3: Edward Jenner and the eradication of smallpox.

You are probably alive because of a British country doctor who lived in the 1700's.

(This is part of a occasional series. The first installment is here).

I have a small ring-shaped scar on my left shoulder, as does everyone else my age. If you were born after 1972, you don’t. Read on to find out why this is, why ‘vaccination’ literally means ‘from a cow,’ and why Edward Jenner, a physician who worked in the English countryside in the 18th and early 19th Century, is said to be the person who saved more lives than anyone who has ever lived.

(photo from Cleveland Clinic)

The scar on my shoulder is from the smallpox vaccine. Smallpox was a terrible disease that ravaged the world for centuries, killing 30% of its victims (60% of its unfortunate child victims) and leaving many of its survivors with grotesquely scarred faces. Some were left blind. To view an extremely graphic image of a scarred child’s face, look here.

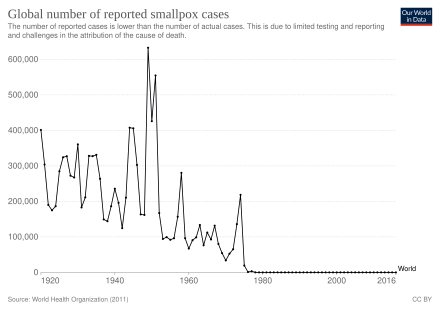

As recently as the 1950’s, an estimated 50 million smallpox cases occurred annually worldwide.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 2 million died of the disease in 1967, although those deaths mostly occurred in poor countries without good public-health systems. Smallpox was declared eradicated, by WHO2 in 1980. It had been eradicated in the US in 1970, which is why Americans younger than 50 haven’t been vaccinated for it. By 1972, the US health establishment officially decided the (very small, but non-zero) chance of side effects from the vaccine outweighed the (zero) chance of getting the disease.

In the past, though, smallpox had been one of the most terrible scourges ever faced by humankind. It killed half a billion people during its last century of existence. It didn’t discriminate by class, either. It killed six European monarchs (Louis XV of France, for one).

Smallpox originated in Africa and Asia, after an animal virus infected humans there (Egyptian mummies from 1500 B.C. show evidence of the disease.) Native Americans were evidently ‘naive’ to the virus, which destroyed wide swaths of their population when it was introduced to them by European settlers and explorers.3

For centuries, physicians from various cultures had practiced inoculation, also known as variolation (for variola, a synonym for smallpox), in which pus from a smallpox blister was purposely rubbed into a cut in a healthy patient’s skin4, in order to cause a (hopefully mild) case of smallpox, as it was known that having had smallpox made one immune to further bouts of it5. This was a dangerous procedure, and many patients developed severe, sometimes fatal, smallpox cases as a result of their inoculation.

Jenner, the eighth of nine children of a British clergyman, was a very good scientific observer.6 He realized that milkmaids didn’t seem to contract smallpox. Legend has it that he asked a young milkmaid if she knew why she and her peers seemed immune, and she replied, “because we have had cowpox.” Cowpox was a mild form of smallpox that infected cows. Milkmaids caught cowpox from the cattle they milked, which seemed to then render them immune from smallpox.

(photo from Getty Images)

Jenner’s first experiment was to take matter from a milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes’s7 cowpox blister and inject it into both arms of his gardener’s healthy son, James Phipps.8Jenner called this procedure 'vaccination,’; vaccine literally means ‘from a cow’. The boy developed a fever but no serious illness. Later, Jenner deliberately “challenged” Phipps with smallpox (in other words, injected pus from a smallpox sufferer into a wound on the boy’s arm), and he did not become ill. Jenner repeated this experiment with at least 17 other subjects, including his own infant son, and all showed immunity to smallpox.

Jenner wrote a paper about his discovery of vaccination and, by the standards of those days, it “went viral,”9 since people were frantic to find a safe way to protect themselves and their children from smallpox.

Even though this was the first type of vaccination, there were already plenty of skeptics, what we would call “anti-vaxxers” today, but the treatment proved so successful that their objections were soon swept aside. The practice was eagerly adopted by many national leaders, including France’s Napoleon Bonaparte.10 Benjamin Franklin had long promoted the more dangerous, but still more-effective-than-nothing, practice of inoculation in the US, thus preparing the ground for the acceptance of vaccination in America, and the first US vaccination occurred in 1799.

(Graph from Wikipedia)

Jenner is said to have saved more lives than any other single person who has ever lived. Given that smallpox killed hundreds of millions of unvaccinated people even after Jenner’s discovery, it seems reasonable to think that most of us are alive today because of him. Had there been no vaccination, it only takes one of our ancestors dying of smallpox to prevent our own birth. This isn’t to say no one would be alive today if not for vaccination, but simply that the many random forks of chance that led to our individual lives would probably have been disrupted were it not for him. There would still be billions of humans on earth, just probably not you or me.

I’m thankful for that little round scar on my arm, and if you are 50 or younger, I’m thankful you didn’t even need that. Thanks for reading

.

The numbers vary wildly, depending on the source. This statistic (from Wikipedia) disagrees with the chart that comes near the end of the article you’re reading now, which is also from the same Wikipedia article. Let’s just say lots of people died from smallpox throughout its history.

The United States recently withdrew from WHO. We can debate the wisdom of this another time. (Spoiler alert: It was very dumb). I didn’t write this post in response to recent headlines, I had long planned for Jenner’s story to be next in this series…

Historians now think that the very first European contacts in the late 1400’s and very early 1500’s led to huge smallpox plagues among indigenous communities, which left large areas of the Americas, which had recently had thriving populations, almost depopulated, making European conquest even easier than it would have been otherwise. This is not to mention the historical practice of deliberately infecting native populations by providing them with smallpox-infected blankets.

Ew.

Though the mechanism was unknown, as neither viruses nor the workings of the immune system had yet to be discovered.

He had studied European cuckoos, for example, whose mothers practice ‘nest parasitism,’ meaning they lay their eggs in other species’ nests. Jenner discovered that the baby cuckoos push their nestmates out of the nests, utilizing a special hollow in their backs. Previously, it had been believed that the mother cuckoos did this murderous task.

Fun fact: According to Wikipedia, Sarah Nelmes had caught cowpox from a cow called Blossom, whose hide now hangs on the wall of the St. George's Medical School library.

Whether this was an ethical experiment is certainly open to question, but in Jenner’s defense, he soon repeated it on his own infant son.

See what I did there? Dad joke.

Napoleon had his armies vaccinated. He was so grateful to Jenner, with whose nation he was at war, that he released two British prisoners at Jenner’s request.